The History of Muddy Waters

McKinley Morganfield was born on April 4, 1913 near Rolling Fork in the Mississippi Delta. His grandmother called him “Muddy” from his habit of playing in mud puddles… Years later, on becoming a musician, the “Waters” part of his name would be added.

Muddy’s father, Ollie Morganfield, was a ‘muleskinner’, meaning he hauled logs from cleared land. Ollie was also an accomplished blues musician in both singing and playing guitar. His mother, Berta Grant, died when Muddy was very young. His grandmother, Della Grant, then took him to Clarksdale, where she had family. Muddy did not see his father for many years.

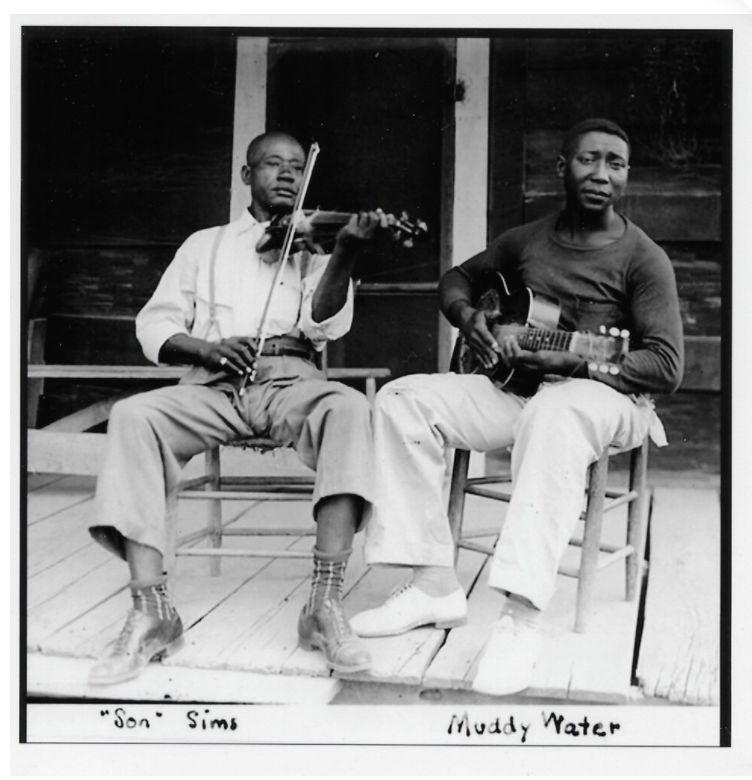

Muddy’s grandmother settled with the three-year old Muddy on Stovall Plantation outside Clarksdale, the largest town in the Delta and a magnet for blues musicians such as Charley Patton and Robert Johnson. Muddy started working in cotton fields at the age of eight. As a teenager, he saw local legend Son House perform and bought a guitar. Muddy began to play bottleneck slide guitar at dances and picnics., in juke joints and at rent parties around Clarksdale, often with fiddler Henry “Son” Sims. A well-regarded tractor driver, Muddy supplemented his field work by fur trapping and selling moonshine whiskey.

Muddy often partnered with his friend Mose “Brownie” Emerson on house parties, charging a nickel entry fee and providing live entertainment and moonshine till dawn.

In 1940, Muddy traveled to St. Louis. He knew of blues artists based there, such as Lonnie Johnson, and Roosevelt Sykes, many of whose records he owned. He met up with Henry Townsend, a Mississippi-born musician who played open-tuned slide guitar, and who is a key figure in the St. Louis bar scene. After a few months of failing to get work as a musician, Muddy returned to Stovall.

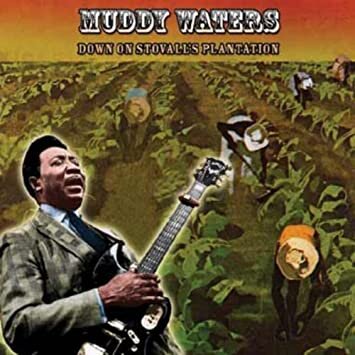

In 1941 Alan Lomax, a folklorist in the Archive of American Folk Song at the Library of Congress, and John Work, a professor in the music department at Fisk University, traveled to Clarksdale to record ‘The musical habits of a single Negro community in the Delta.” Lomax, initially looking for the legendary Robert Johnson (whom he found out had died) was directed to Muddy and recorded Muddy’s classic Delta country blues songs “I Feel Like Going Home” and “I Can’t Be Satisfied.” At his home in Stovall. Muddy later receives $20 and two copies of his recording. He then resolves to become a full-time musician.

These recordings were issued as “Down on Stovall’s Plantation” on Testament Records. The album was re-issued in 1993 on Chess Records as “The Complete Plantation Recordings”. The re-release not only brought new fidelity to the music, but the producers wisely included between musical tracks conversations between Lomax and Muddy that are as fascinating as the music. The album was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame in 2001 as a Classic of Blues Recording.

This seminal occasion in American (and global) music is commemorated by a Mississippi Blues Trail Marker 2.5 miles east of the festival site.

In 1943, Muddy took the train from Clarksdale to the city that would become his lifelong home base, Chicago, home to the largest population of Mississippians outside the state. Performing frequently in South Side clubs, Muddy signed with Chess Records; assembled a series of amplified electric blues bands with talented sidemen who would go on to form their own bands; and scored 15 hit records in the 1950’s. Muddy created the sound known as “Chicago blues,” the Bible of modern rock’s riffs, lyrics, and attitude. In 1960, his appearance at the Newport Folk Festival and subsequent extensive American touring, inspired a young generation of white American blues musicians, including Mike Bloomfield, Paul Butterfield, and Johnny Winter.

In 1958, Muddy visited England with the American Folk Blues Music Festival and shocked ‘folk’ audiences with his bottleneck blues played on electric guitar. A subsequent British blues revival started a musical revolution, with bands like The Yardbirds and The Animals, and musicians like Eric Clapton learning and playing Muddy’s licks, riffs, and lyrics for a new, younger, white audience. The Rolling Stones, naming themselves for one of Muddy’s songs, scored their first hit in the U.S. by re-working Muddy’s first hit: “I Can’t Be Satisfied” which evolved into “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction.”